344 pp

SportsBooks

£17.99

The Rebel Tours is a history and analysis of the seven cricket teams to tour South Africa between 1982 and 1990 in defiance of the international sporting boycott. These unofficial national teams played so-called “Tests” and “One Day Internationals” against “official” Springbok XIs.

The tours’ genesis was the inclusion of the Cape Town-born Basil D’Olivera in the England squad to tour South Africa in 1968. Prime Minister Vorster declared that the team was “not the team of the MCC but the team of the anti-apartheid movement.” The 1968 tour was cancelled but the 1970 South African tour to England was retained though also eventually cancelled due to the threat of civil disorder. In the event, a Rest of the World XI played, featuring five South Africans and captained by the West Indian Garry Sobers. Nobody objected to that.

Vis-à-vis apartheid, cricket was always more contentious than rugby because of the international teams of India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and West Indies. With the exception of Maoris in the New Zealand team, there were no race concerns in the oval ball game. Golfers and tennis players – white ones, anyway – could visit South Africa without punishment. As May’s chronological account makes clear, always there were double standards and Pharisaisms. Cricketers considered as rebels and traitors by some were seen as pioneers and crusaders by others. In the 1970s touring sides could field multi-racial teams but Springbok XIs, unlike the issue itself, were either black or white.

May’s reporting is fair-minded, with neither side coming out very well. Peter Hain considered D’Oliveira to have come out of the 1968 fuss “very badly,” thinking of him as having potentially condoned the all-white Springbok team by playing against them for England. Those on the inaugural 1982 tour were uniformly banned for three years. It ended Geoffrey Boycott’s 108-Test career. The Warwickshire wicketkeeper Geoff Humpage had featured in only one match on tour but never played again for England. Those three years covered England matches against the “black” countries and meant the players would be available for The Ashes in 1985.

Apparently minded towards touring in 1982, the England all-rounder Ian Botham was dissuaded by his advisors because his heroics in the Ashes series of 1981 had made him a superstar and lucrative sponsorships had followed. In a national newspaper he gave his reason for declining the tour because “I could never have looked my mate Viv Richards in the eye this season…” But for most cricketers the sums offered for playing in South Africa were impossible to decline. May describes how many of the players involved “ignored or declined my enquiries; only one offered the unimprovable, irony-free response, ‘What’s in it for me?’” That is the attitude that led many to accept South African money, which, it turned out in 1986, was funded by the South African Cricket Union and its sponsors via 90 percent tax rebates from the ruling National Party.

Despite that revelation, the tours continued. It was not entirely disingenuous of players to say that they went to South Africa as professional cricketers to earn a living, not to condone or condemn apartheid. They broke no laws by playing cricket in South Africa. “Now just supposing the Russians played cricket…” wondered George Gardiner MP after Mrs Thatcher had promoted a British Boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Michael Brearley’s response to such arguments was that “the system of government (in Russia) is not designed to oppress people on the basis of birth or race. South Africa’s is.” Despite the hype, rebel teams were typically half-first XI/half-second XI in representation and playing strength. Players such as Peter Willey – an effective England all-rounder but no Botham – were discussed in awed tones by South African newspapers.

The cricketing consequences were far-reaching and affected the balance of playing power in the 1980s. Just as the England team was weakened after 1982 by a three-year ban on the rebels, the Australian team was decimated by a combination of retirements and rebel tours, reaching its nadir in the mid-1980s. The West Indies of that decade, however, had virtually a spare team of outstanding (and impecunious) players that could not force their way into the first-choice Test squad. Alvin Kallicharan played for Transvaal and was immediately banned by the West Indies. With nothing to lose, he captained a rebel team in 1983. The rebel West Indian team represented what May calls “the greatest coup and the deepest affront.” Were they showing that blacks could play cricket as well as, or even better, than whites or were they selling their souls to the Apartheid government? The 1983-84 team captained by Lawrence Rowe was the only rebel side to win a “Test” series in South Africa but many of those players faced professional and personal rejection when they returned to the Caribbean.

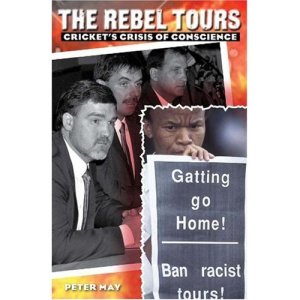

Mike Gatting went to South Africa in 1990 as captain of what turned out to be the last unsanctioned tour, when Nelson Mandela’s release was imminent. As Ian Wooldridge wrote, “Mike Gatting finds himself in the wrong place at the very wrong time.” Pictured on the book’s cover, Gatting, Emburey and Graveney of the 1990 team all later assumed important roles in English cricket. That is just one of the many ironies in this book, which is throughly well-researched even if so many of the dramatis personae refused to speak to the author.

The great player and commentator Ritchie Benaud once remarked, “The Titanic was a tragedy, the Ethiopian drought a disaster, but neither bears any relation to a dropped catch.” In cricketing terms, it is a tragedy that the brilliant South African team of the late 1960s/early 1970s did not have the opportunity to show its skills more often on the international stage. But Benaud, who managed an International Wanderers XI in South Africa in 1976, and others would probably admit that Apartheid was a greater and far more damaging tragedy.

[…] have put a full-length review here of this fascinating book. Peter May has done a very good job in covering the events and issues of […]

[…] PS (13 Jan ‘10) TLS reviewer Stuart George has now pasted an extended version of his review on his blog. […]

Re Peter Hain saying ‘D’Oliveira to have come out of the 1968 fuss “very badly,” he later revised this view – the comment below is from an article he wrote recently (http://basildoliveira.com/testimonials/peter-hain-mp/)

“Basil himself disappointingly remained aloof from the struggle, and activists criticised him for being an ‘Uncle Tom’. But, in hindsight the irony is that if Basil had been in any sense ‘political’, as we wanted him to be, there would have been no ‘D’Oliveira Affair’. He probably would not have enjoyed the universal support of the cricketing community, nor would his treatment have provoked the universal outrage it did among middle Britain, which proved such a great assistance to our campaign. The cancellation of the 1970 tour might well not then have happened and getting South Africa expelled from world sport, with its huge psychological and political impact upon white South Africans, might have taken much longer to achieve. Who knows how much longer, in turn, apartheid would have lasted?

For that reason the anti-apartheid struggle owes Basil D’Oliveira a great debt of gratitude. And I can now salute his memory; his courage in overcoming adversity to leave the land of his birth and triumph as an England cricketer; and his perhaps unwitting role as an ally in the victory of good over evil that saw the transformation to a non-racial democracy in South Africa today, when young Basil D’Oliveiras can, and indeed do, represent the country of their birth in the beautiful game of cricket.”

So no, I do not think that the idea that neither side came out it very well is fair. South Africa and MCC behaved disgracefully; on the other hand, Basil himself and the anti-apartheid movement were fully vindicated.

Thank you for your comment.

I read recently Peter Oborne’s Basil D’Oliveira: Cricket and Conspiracy and there is no doubt that D’Oliveira conducted himself magnificently. He is an extremely intelligent and dignified man, which is more than can be said for some of the other people in this sordid tale…

Peter Hain is perfectly entitled to have revised his view. Frankly, he was wrong at the time. That is why I said that neither side emerges well from Peter May’s book. We all have the benefit of hindsight.